Hello!

Welcome to my third newsletter and the first one of 2022. Happy New Year! Thanks for signing up.

I would love it if you could forward this to one person who might be interested in knowing more about adapting to climate change in 2022. This is a new project and I am keen to get the word out.

In the last week I have been busy updating the reading list for my course at UCL this term and submitting a large grant proposal. Both of these have led to me reading lots of research papers about measurement. The crux of all the research is what we choose to measure is not a neutral, purely technical exercise. It reflects power relationships and also shapes what people do and how they understand the thing that is being measured. (If you are taking my course please still come, there is a little more to it…)

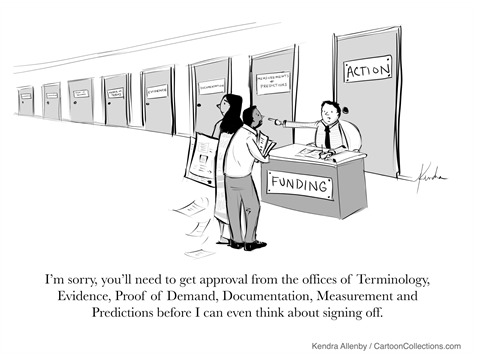

In the world of adaptation, measurement has been emerging on the scene as a big - if somewhat niche - topic. The argument goes that with reducing greenhouse gas emissions we all have clear metrics and targets in mind, such as units of carbon dioxide and a temperature goal - trying to keep warming to 1.5 degrees. For adaptation it is not clear what measures success or even what success looks like. This makes it more difficult to assess how well countries are doing and to rally behind more money and faster progress.

There have long been tensions in measuring adaptation. There are technical debates about what concepts to use and how to manage the fact that the climate we are trying to adapt to is changing at the same time as we are trying to measure progress. By the time we have adapted to strong storm surges along the coast, the storms might have got even worse. But there are also conflicts over whose agenda measurement serves.

Is it for the international funders to add up the impact of their investments?

Is it for development agencies to report back to their parliamentarians that money has been well spent?

Is it for national governments or local communities to help them understand what is effective and what they should do differently?

Each of these needs a different approach. The Paris Agreement contained a commitment for the first time to a global goal for adaptation – an aspirational target for all countries - and since then countries and those working within the UN system have been trying to work out what on earth that means. The negotiations in Glasgow went further in establishing a work programme to develop the detail.

Across all this is also the reality that what we know about adaptation in different places is very uneven, as is who is creating and communicating this knowledge: as Chandni Singh from IIHS argues “it is a very white world out there”. I recommend reading the rest of her blog too.

So, adaptation measurement is a hot topic. The key issue to watch will be whose interests win out in the goal and other measurement efforts, and how much the process will support understanding and improving adaptation versus producing another long report for the shelf.

This week’s read: Great Adaptations by Morgan Philips, featured in Nature!

Who for? Those new to climate change adaptation.

TLDR: Great Adaptations is a quick read for those interested in an overview of the types of adaptations happening across the world and some of the common challenges they face. It raises more questions than it answers and this is the purpose of the book, to start a conversation. It left me thinking about two major adaptation priorities for 2022 (and beyond). (1) How to shift power and politics to allow for new adaptation responses that move past the status quo – local action can be inspiring but rarely makes sustainable change at the scale needed. (2) Promoting approaches that help communities and policymakers think outside current norms of what the climate will look like in the future. It is so hard to imagine and plan for what we cannot see.

There are very few books on adaptation for a wider public and this one is an attempt to fill this gap. It was a fascinating read. I have to admit in these social media times I can sometimes struggle to keep going with a book-length argument. But this one is well written and engaging with great images and personal stories. The central thesis is that the climate movement and campaigning organisations need to pay more attention to ensure adaptation happens when and where it is needed, in a just and equitable way.

Philips takes us through some ‘Great Adaptations’ including examples of a resource centre for farmers in rural Nepal, France’s increasingly effective responses to summer heatwaves, and the managed retreat in Staten Island after Superstorm Sandy. I particularly liked the discussion of ‘coolth’ (the opposite of warmth) and learning about the cool rooms they have set up in Paris for heatwaves and the trend in Doha to air condition the pavement and outside spaces. This also felt new and interesting to me as it feels very rare to hear these comparisons across the traditional divides of the Global North and South. Adaptation is very different in these contexts but the hazards and potential responses still offer lessons or at least ideas for ways forward.

I work professionally on adaptation and I have sometimes felt overwhelmed with the huge amount to do and the lack of big steps forward. It was heartening to hear stories about some of the more difficult choices around adaptation being made, or at least being considered.

No book on adaptation can sidestep the question of transformation. Transformation is a buzzword amongst the policy and academic community, but also a necessary recognition of the huge steps the world needs to take now to adapt to the climate impacts associated with the current degrees of warming. Most of the case studies in the book are small steps forward, which is unsurprising as this is where most current adaptation practice is focused. Philips asks will more transformative responses need a societal collapse to emerge? Can small seeds such as the Rojavan revolution in Northern Syria show us potential ways forward? Philips concludes with a few suggestions: tell more transformative adaptation stories, engage the public in wider public debate on some of the major adaptation questions facing us, and use deliberation to work through the differing aspirations of groups and individuals.

And finally…

Last newsletter I wrote about understanding the attribution of extreme events to climate change i.e. how do we know if a storm or drought was because of, or made worse by, climate change. There has been an interesting academic paper HOT OFF THE PRESS last month arguing that the sole focus on attribution risks hiding the local social and political conditions that create vulnerability.

Climate change never causes loss or damage independently of the social conditions on the ground in specific places; the degree to which climate change can trigger disaster depends on the degree to which people are already exposed and precarious (Lahsen and Ribot, 2021).

Food for thought.

Thanks for reading and happy January to all!

Susannah

Very interesting as always. I agree fully with the argument that measurement very easily becomes a mechanism of control, and hence is inextricably linked to power dynamics. The development and peacebuilding fields, among others, are grappling with the same thing. Do you know of any examples of locally developed forms of adaptation measurement and monitoring- eg. by local organisations or even governments of especially climate vulnerable countries? This is one potential way that accountability might be transformed.